The Legalization of Medical Marijuana at the Federal Level

Introduction

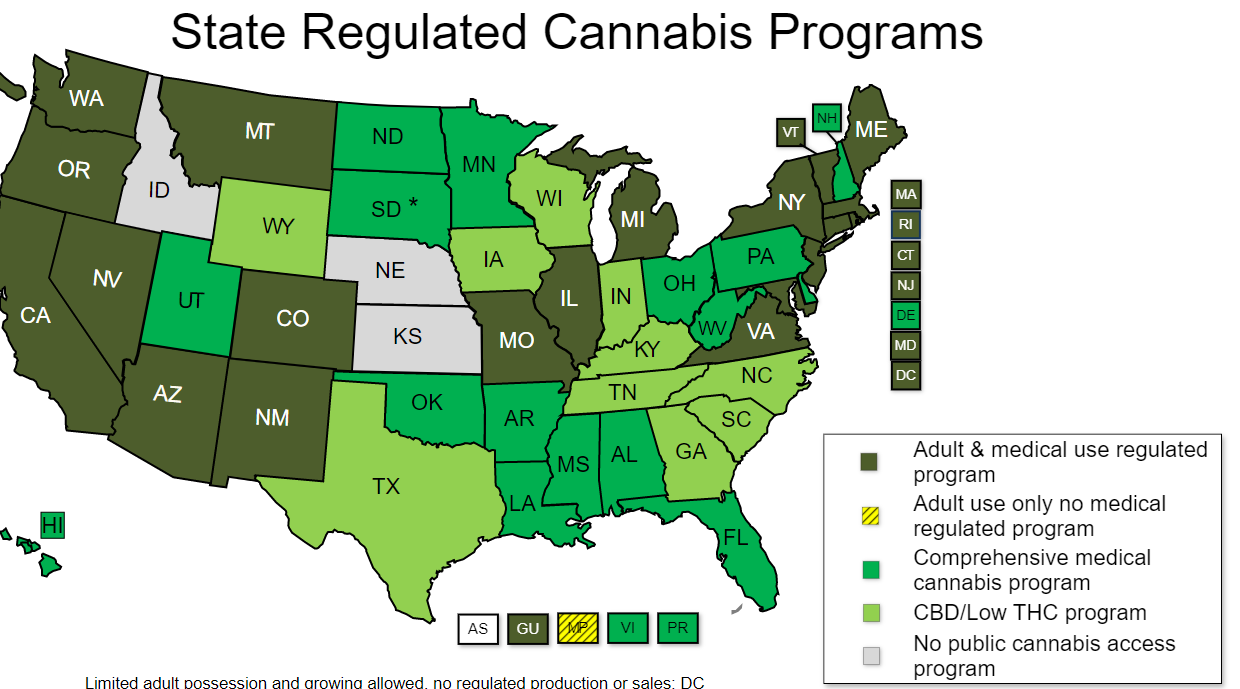

The liberalization of marijuana usage and distribution at the state level has been evolving in the past five decades despite its prohibition at the federal level. In the 1970s, states passed several decriminalization policies, while in the 1990s, laws legalizing patient medical access to marijuana started to get adopted (Reid 69). Recently, several states have been experimenting with legalizing marijuana for recreational purposes. However, policies to decriminalize its use are yet to be adequately adopted on a federal level, and therefore, some states, such as Ohio, have no public cannabis access program. Furthermore, in the Controlled Substances Act, cannabis is still categorized as a Schedule I drug. Schedule I drugs are identified to have a high probability of dependency with no accepted medical use (Chihuri and Li 8). Due to its classification, the cultivation and distribution of marijuana are considered a federal offense. This report provides arguments to support the legalization of marijuana for medical purposes at the federal level. For decades, NIDA was the only organization that was allowed by the American federal government to regulate and distribute marijuana; the monopoly of the agency allowed it to stock low quality marijuana as well as control who conducted studies on the drugs which inadvertenly influenced Americans perception of it.

The evolution of marijuana reforms has led to the adoption of a wide spectrum of liberalization policies across the United States. For example, as of January 1, 2016, 26 states have decriminalized medical marijuana, and 16 states have adopted cannabidiol-only policies that legalize only the medicinal use of specific strains of cannabis. Additionally, 21 states have decriminalized particular cannabis possession offenses as shown in figure 1 (Wen et al. 217). Still, despite the advantages of marijuana, there are numerous inconsistencies in the heterogeneity of policies and the measures of usage. In addition, the policies have significant overlaps as some states have enforced combinations of them. For example, as shown in figure 1, several states legalized marijuana use for recreational purposes, such as Colorado, Washington, Alaska, and Oregon (Howell et al. 128). Nevertheless, despite the positive impact of medicinal prescription marijuana, reforms to legitimize or decriminalize marijuana use are yet to be instituted at the federal level.

Link between NIDA and Poor Research

The lawmakers decided to illegalize marijuana use in patients based on inadequate information. Prior to 2021, the approval of the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) was required when conducting clinical research on marijuana (Purcell et al. para 3). The mission of NIDA is to boost research on the causes, prevention, consequences, and treatment of drug addiction and drug abuse. Therefore, the institute is not mandated to support the medicinal value of drugs. As a result, many studies focusing on the therapeutic benefits of marijuana were either downright denied or changed to fit into the limited mission and scope of NIDA (Purcell et al. para 8). Furthermore, there are no timeline restrictions where NIDA is obligated to respond to proposals; this exacerbated the delays in getting research approval which may sometimes last up to years. The marijuana provided by NIDA has been disparaged for being of inferior quality compared to what is commonly used by medical marijuana patients in the states where it is legal. NIDA-supplied cannabis is inferior because it has significantly higher quantities of stems and seeds, low THC content, high levels of yeast and molds, and low diversity of available strains.

However, despite the inferior quality of NIDA-provided marijuana, NIDA has always been the sole provider of marijuana needed for research purposes in America. The monopoly was upheld by the Drug Enforcement Administration’s refusal to issue more licenses for the farming and distribution of marijuana, a situation that the DEA claims is lawful and in consistency with the the1961 ratified terms of U.N. Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs (Haffajee et al. 502). Nonetheless, the DEA cited the likelihood of diversion from cultivation facilities as justification for the refusal to issue more licenses. Thus, while the congress and critics’ opinions and perceptions of the advantages and disadvantages of the use of medicinal marijuana are founded on research conducted using NIDA cannabis, the results may be misleading (Haffajee et al. 503). Therefore, since the DEA ended the NIDAs monopoly on cannabis cultivation and researchers can openly, freely, and rapidly conduct their research, lawmakers can use these results to inform their decisions on the legitimization and decriminalization of using marijuana for medicinal purposes.

Organizations Supporting Marijuana Usage

Numerous reputable organizations in the United States have issued statements in support of permitting access to medical marijuana, thereby solidifying the medical benefits of the drug. One of the biggest supporters of cannabis legalization in America is the Americans for Safe Access. The American group is dedicated to fighting for the reform of marijuana policies. The group has over 10,000 members across the 50 states of America. Its advocacy focuses on the medicinal use of cannabis to help treat and manage certain conditions. The group was founded by a patient, Steph Sherer, who is dependent on medical cannabis to fight his symptoms (NCSL para 7). Other organizations advocating for marijuana policy reforms include Marijuana Laws, Drug Policy Alliance, and Marijuana Policy Project. Nonetheless, these groups are advocating for both medicinal and recreational use.

In addition to advocacy groups, numerous medical organizations, religious denominations, military veterans, and several legislative bodies have issued statements supporting patients’ permission to access medical marijuana. Medical organizations that have advocated for the legalization of medical marijuana include American Medical Student Association, American Nurses Association, American Public Health Association, and Lesbian Medical Association. Other medical agencies include the National Multiple Sclerosis Society, Epilepsy Foundation, Leukemia & Lymphoma Society, Gay, National Women’s Health Network, and numerous AIDS advocacy organizations (Alharbi para 12). Additionally, Katner highlights several religious denominations in America that have revealed their support for permitting the medical use of marijuana (168). They include the Union for Reform Judaism, the Episcopal Church, the Presbyterian Church (USA), the United Methodist Church, the United Church of Christ, and the Unitarian Universalist Association.

Similarly, military veterans’ organizations, medical bodies, and legislative bodies have advocated for removing marijuana from the Schedule I drugs list and being reclassified as a Schedule III drug. They include the American Legion, American College of Physicians and American Medical Association, National League of Cities, National Conference of State Legislatures, and U.S. Conference of Mayors (Katner 167). Furthermore, the National Association of Counties has asked congress to enact legislation promoting federalism principles in the control of the cannabis business. Finally, other organizations, such as the National Sheriffs’ Association and the American Bar Association, have also asked to reschedule marijuana drugs (Reid, 169). Conclusively, marijuana legalization for medicinal purposes has been advocated by religions, medical professionals, legislatures, and the military. Most of these advocacies have been backed by research and personal and professional convictions. As pillars of the community, these agencies reflect the needs of society; therefore, their advocacy should not be overlooked. As a result, congress should consider the reform of marijuana policies at a federal level.

Organizaitons Condemning Usage of Marijuana

Nonetheless, some of the most influential agencies in the medical field do not advocate for the rescheduling of marijuana or its legalization for medicinal purposes. Several prominent medical bodies have advocated for the rescheduling of marijuana to allow for better-nuanced approaches to the regulation and legislation of marijuana. They include the American Academy of Family Physicians, the American Cancer Society, the American Society of Addiction Medicine, and the American Psychological Association (Reid 170). These agencies are advocating for the reform of policies regarding marijuana because they have noted the existing obstacles when researching cannabis. Therefore, their advocacies are not directed at the permission of cannabis for recreational or medicinal use but for research purposes only. These agencies inform the usage of drugs in the medical field; therefore, their lack of support for the reforms raises concerns about the need for marijuana in medicine. However, with more research, the groups may appreciate the effects of medicinal marijuana and advocate for the reformation of its policies at the federal level.

Conclusion

The legalization of marijuana for medical purposes is hindered by insufficient research on its merits. Most states have adopted reforms that allow its usage for medicinal purposes, while a few other states have legalized its use for recreational purposes. However, at the federal level, marijuana is currently considered a Schedule I drug with a high potential for addiction. As a result, the distribution of drug has been illegalized. Nonetheless, various agencies representing the legislature, religions, military, medical profession, and public advocacy groups have spoken up in favor of the rescheduling, distribution, and usage of marijuana for medicinal purposes. Nevertheless, some agencies in the medical field, like APA, do not support the legalization of marijuana use even though they support its rescheduling. According to the agencies, there have been discrepancies in research involving marijuana, and its rescheduling could strengthen its studies. Similarly, for decades, NIDA has had total control over research marijuana, affecting the research’s integrity. Conclusively, studies conducted on the merits and demerits of marijuana have been compromised by the laws surrounding the drug and may have affected lawmakers’ perceptions.

Works Cited

Alharbi, Yousef N. “Current legal status of medical marijuana and cannabidiol in the United States.” Epilepsy & Behavior 112 (2020): 107452. Web.

Chihuri, Stanford, and Li, Guohua. “State marijuana laws and opioid overdose mortality.” Injury epidemiology 6.1 (2019): 1-12. Web.

Haffajee, Rebecca L., MacCoun, Robert J. and Mello, Michelle M. “Behind schedule reconciling federal and state marijuana policy.” N Engl J Med 379.6 (2018): 501-4. Web.

Howell, Khadesia, Washington Alice, Williams Peters A., et al. “Medical Marijuana Policy Reform Reaches Florida: A Scoping Review.” Florida public health review 16 (2019): 128. Web.

Katner, David R. “Up in smoke: Removing marijuana from schedule I.” B.U. Pub. Int. LJ 27 (2018): 167. Web.

Purcell, John M., Passley, Tija M., and Leheste, Joerg R. “The cannabidiol and marijuana research expansion act: Promotion of scientific knowledge to prevent a national health crisis.” The Lancet Regional Health-Americas 14 (2022): 100325. Web.

Reid, Melanie. “Goodbye Marijuana Schedule I-Welcome to a Post-Legalization World.” Ohio St. J. Crim. L. 18 (2020): 169. Web.

State medical marijuana laws. NCSL, 2022, Web.

Wen, Hefei, Hockenberry, Jason M., and Druss, Benjamin G. “The effect of medical marijuana laws on marijuana-related attitude and perception among U.S. adolescents and young adults.” Prevention Science 20.2 (2019): 215-223. Web.