Phenomenology of 4th Amendment to US Constitution

Introduction

As a society, people live in a time where one’s whole life can be looked at on social media, pictures stored on many different smart devices, and communication, both private and professional, is done on the internet. A vehicle may be searched when being driven across the border from the United States to Canada or Mexico. These are just a few items that can be searched for law enforcement purposes without a warrant. The public should be aware that any activity that they engage in, especially if it is on social media, can be searched by law enforcement at any time when criminal activity is suspected.

Problem Statement

It is not known how or to what extent the public knows about the Fourth Amendment as it pertains to warrantless searches. For example, border vehicle searches, electronic device searches, or exigent circumstances, specifically when they are legal versus not legal.

Purpose Statement

The purpose of this research is to examine the extent of the public’s knowledge of the Fourth Amendment and their perception of warrantless searches.

Hypothesis

The working hypothesis for this research project is based on the assumption that public knowledge of the Fourth Amendment is high. In addition, it is assumed that the public is unequivocal about the unreasonableness of searches without a warrant.

Literature Review

An intriguing part of the research project is to place the problem of unreasonable searches in the context of the Fourth Amendment into academic discourse. As the text of the Fourth Amendment states, “The right of the people to be secure in their persons, houses, papers, and effects, against unreasonable searches and seizures, shall not be violated, and no warrants shall issue, but upon probable cause, supported by oath or affirmation, and particularly describing the place to be searched, and the persons or things to be seized” (Fourth Amendment, n.d.). The Fourth Amendment was created to protect citizens of the United States from unlawful search and seizure by the government. For decades, it seemed an appropriate and fundamental practice to protect the interests of citizens from law enforcement misconduct. However, since the creation of the Fourth Amendment, the evolution of technology and time has necessitated a reinterpretation of the Amendment as to when a search and/or seizure warrant is or is not required. Over the years, there have been several cases that have found police conducting unreasonable searches and seizures. This literature review looks at the Fourth Amendment and when police can and cannot search without a warrant. It will also cover several cases that have gone before the Supreme Court to determine if searches conducted without a warrant were reasonable and lawful.

Reasonable Searches

Although the Fourth Amendment protects an individual’s right to privacy and freedom from government orders, there are cases where a search without a warrant is lawful (LII, 2020). Such searches fall into seven categories:

- Arrest for committing a felony in a public place

- Exigent circumstances.

- Reasonable searches and good faith

- A traffic stop on reasonable suspicion

- Search directly related to a lawful arrest

- Suspects in ongoing criminal activity

- Certain roadblocks

Reasonable searches should not be seen as a contradiction to the existence of the Fourth Amendment, but rather it is an exception, only affirming the need to protect citizens. In fact, reasonable searches, as has become clear, do not require law enforcement agencies to use warrants when the search involves a person who is suspected of disorderly conduct (LII, 2020). In all other cases where no such suspicion exists, law enforcement agencies are required to have warrants on hand to protect citizens from unreasonable and lawful searches.

Supreme Court Cases

An academic analysis of the Fourth Amendment problem, with its practical exceptions, is impossible without an examination of existing case law. In United States v. Jones, the Supreme Court held that a search without a warrant of packages that were lawfully seized in search of a car and stored in a DEA warehouse for three days did not violate the Fourth Amendment requirement. The Court’s ruling extended the Fourth Amendment exception to the search warrant requirement for packages set forth in United States v. Ross. The Court held that a search of packages found during a lawful automobile search does not require a warrant if the police have reason to believe that the packages conceal the object of the search for probable cause (Justia, n.d.; Schwinn et al., 2017). In other words, in these cases, the police officers’ actions were fully classified as lawful only because they had a suspicion that the citizen and/or his property posed a danger. Nevertheless, in extending the Ross exception to the facts of the Johns’ case, the Court indicated that a search without a warrant of the packages found in the cars, like a search without a warrant of the cars themselves, would not be considered reasonable merely because of the delay between the seizure of the packages and their search three days later. The fact that the car containing the packages had been in DEA custody for three days should have been sufficient to determine that a search warrant was indeed necessary, and thus the search should have been found unreasonable (Bobber, 1985).

In discussing the applicability of the Fourth Amendment, one must be particularly attentive to the specific dilemmas surrounding these issues. In particular, the determination of whether police officers can read text messages is of great interest. In People v. Diaz, an officer found a cell phone in the hoodie pocket of a man who was arrested for selling drugs to a police informant (Justia, 2019). Prior to the arrest, the officer tapped the conversations through a wireless transmitter. The cell phone was seized after Diaz was arrested, the officer searched the phone’s text messages without a warrant and found the message “6 4 80,” which meant six pills for $80. Because the phone was the defendant’s personal property and was found on him at the time of his arrest, the Court found the search constitutional. In Ohio, the Ohio Supreme Court ruled in Ohio v. Smith that unless the officer’s safety was threatened or an emergency situation arose, the Fourth Amendment prohibits searches of cell phones seized during an arrest without a warrant (Ward, 2011). Case results are divergent as to whether the extensive electronic information contained in a cell phone gives the owner of the phone a right to privacy. An Ohio judge held that a cell phone’s ability to store a large amount of data gives cell phone owners a higher level of privacy, which in turn requires a warrant. This is because preventative measures can be taken after a cell phone has been seized to ensure that the data on the phone is not lost or erased.

Proposed Solution

As has become clear from the literature review, the Fourth Amendment can be applied or partially violated in some cases, that is, it meets the ambiguity of enforcement. Such ambiguity is widely recognized in academic discourse. For example, Tokson (2020) writes that the application of the Fourth Amendment to protect the interests of citizens occurs when the government —represented by law enforcement or the judiciary — violates their right to privacy. At the same time, the Supreme Court does not explain the scope of this invasion of privacy. It is precisely this kind of reticence, apparently favorable to the authorities, which creates positive opportunities for an overt violation of the Fourth Amendment.

Meanwhile, the ability to understand and interpret the Fourth Amendment as it applies to search and seizure can affect the outcome of a case. In an ideal world, an officer should be able to obtain a warrant before every search and seizure, but that is only sometimes the case. There are times when an officer does not have time to wait for a warrant, such as in an emergency, or evidence may be destroyed before a warrant is obtained. If a warrant cannot be obtained, the office must prove that there was reasonable and lawful cause for the search and seizure without a warrant.

In all of the cases discussed above, the foundation of the legal dilemma lies in the plane of rights between the personal and the collective. On the one hand, the state consists of individuals who knowingly surrender some of their freedoms in exchange for living within a formalized structure, that is, the state guarantees their protection in exchange for loyalty. On the other hand, the state can never provide equal protection for absolutely every citizen, especially in the cases of superpowers with large populations. This is why such a dilemma will persist until the legal practice of statehood is radically altered.

Implications of Social Policy

The literature search has demonstrated that the Fourth Amendment’s applicability problem is not universal and can be interpreted depending on the context. A citizen’s fundamental right to the protection of personal interests can be comparatively quickly challenged when public safety is threatened. It follows that between the personal and the collective, states naturally choose the collective, unhindered by the violation of the individual’s privacy. Clearly, over time, new situations will arise that have not been faced before, and the Supreme Court and legislators will have to work together to ensure that citizens’ Fourth Amendment rights evolve in accordance with changing circumstances. In fact, by now, there have already been quite a few such cases in which there has been an inconsistency in the enforcement of the Fourth Amendment. Several of them are cited by Becknell (2021), who, among other things, writes about the story of a home search in the apartment of a high school student who had a gun in his background during distance learning. This and similar examples demonstrate how sensitive and thin the line is between the protection of an individual citizen’s interests and public safety, even in cases where such safety is not dictated by actual facts.

Methodology

To test the hypothesis of how the public perceives the Fourth Amendment and their knowledge of the warrantless search, cases in which the validity of the warrantless search is in question will need to be researched as well as the development of a questionnaire to ensure that all demographics are correctly identified to include race and age to assist in finding out where the individuals surveyed get their news and follow up with a six-point opinion system of general as well as more specific information in the subject as well as knowledge of cases the involve the issues related to the warrantless search.

Target Population

The target population is essentially anyone since almost everyone has access to the news, whether on television, the internet, or the newspaper. The results of the survey will be more accurate if a large part of the target population participates in completing the survey.

Sampling

To assess the hypothesis, it will be necessary to be able to contact the most significant possible number of people within each demographic. It is known that most people watch or read the news or use the internet.

Instrument

The instruments used will primarily be the internet and hard copy. Links to the survey with access codes will be available as well as paper copies of the survey will be available for individuals that have limited access to the internet and social media. The survey will include both standard demographic information questions as well as questions specific to the subject matter.

Findings

The purpose of this research project was to investigate public opinion regarding the Fourth Amendment, which prohibits law enforcement searches without an appropriate warrant. This amendment in the Bill of Rights creates ambiguous implications for personal and national security (Bobber, 1985). On the one hand, it protects privacy interests and prevents searches of citizens unless there is a specific court order to do so. On the other hand, national security and intelligence issues aimed at protecting state interests are more difficult because law enforcement agencies do not have unfettered access to data of heightened interest. As a consequence of this paradox, it was necessary to conduct a public opinion survey not only to determine general trends on the issue but also to look for potentially hidden data between demographic groups in how they were inclined to respond.

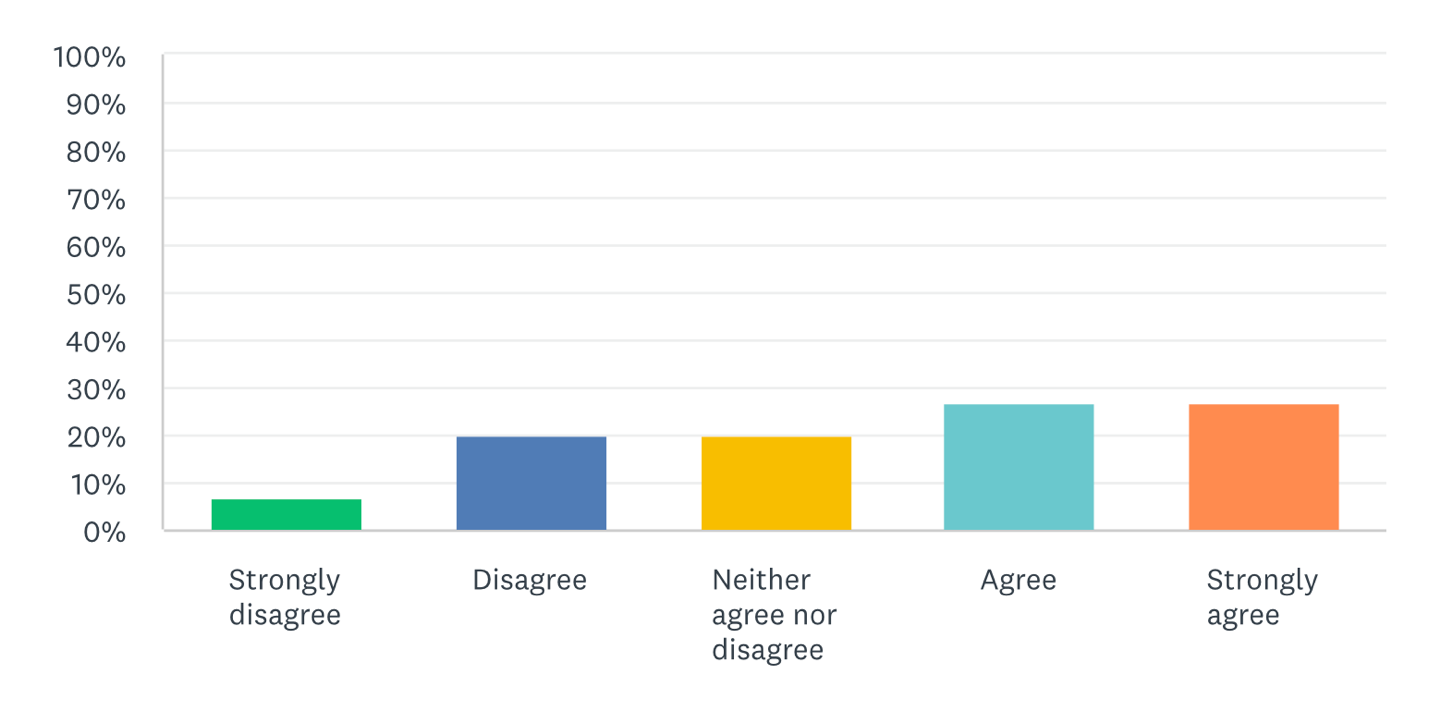

For a sample of respondents (n = 15), represented almost equally by males and females, it was found that everyone was familiar with the Fourth Amendment. More intriguing results were found in the situational scenario questions, which asked respondents to agree or disagree with a statement. In particular, Figure 1 shows that respondents tended to be ambivalent about the need for a search warrant regardless of the situation. However, most of them certainly felt that a warrant was necessary. Apparently, the phrase “for any reason” for participants may have been associated with emergencies, in which 86.47% of participants responded that a warrant was not required for searches. This is further supported by the fact that 73.34% of respondents said a warrant might not be required if a police officer has probable cause to search an individual.

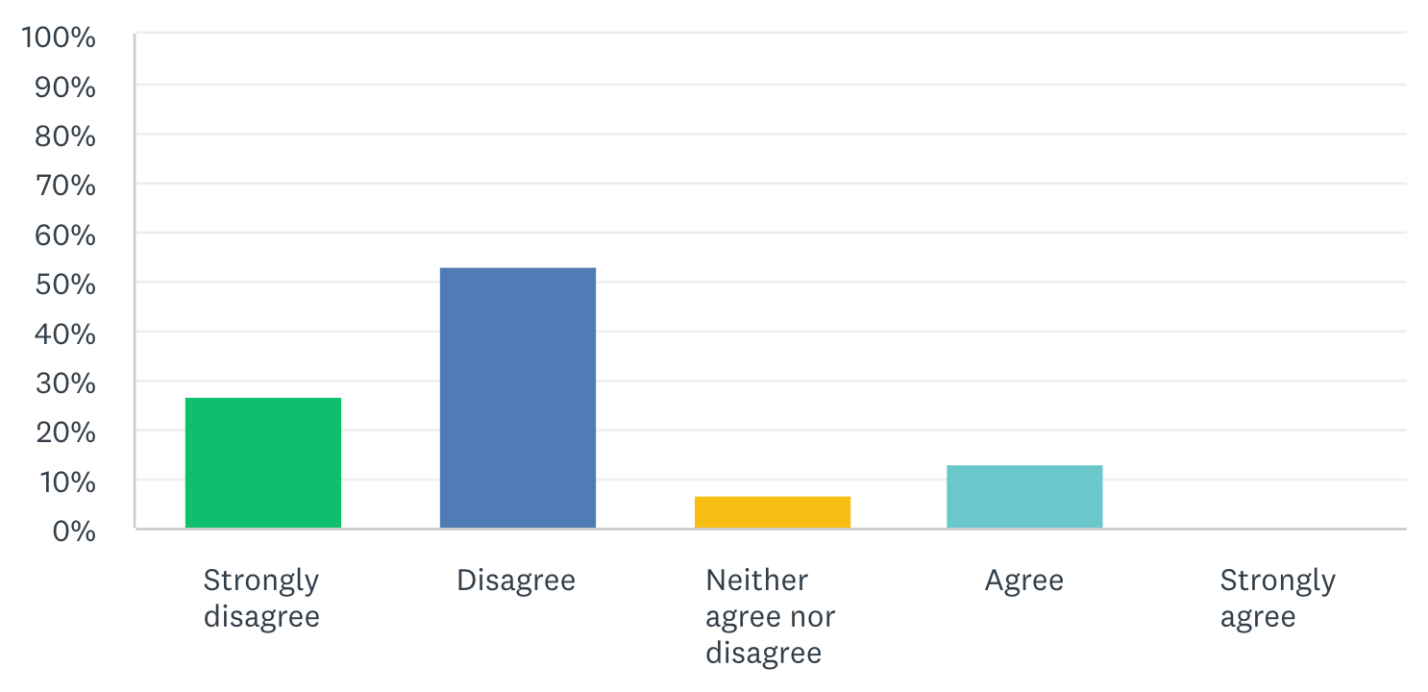

On the other hand, the majority of survey participants (80%) called it illegal for law enforcement agencies to wiretap personal phone calls without a warrant. From these results, it can be concluded that in peacetime, most people prefer to protect their own interests, but when critical situations arise, the state’s interests outweigh them. However, it can be cautiously assumed that society perceives some tacit contract between it and the state, according to which conducting searches without warrants in critical situations are acceptable, but wiretapping is not. In other words, respondents were willing to consent to government actions contrary to the Fourth Amendment when those actions did not directly affect them.

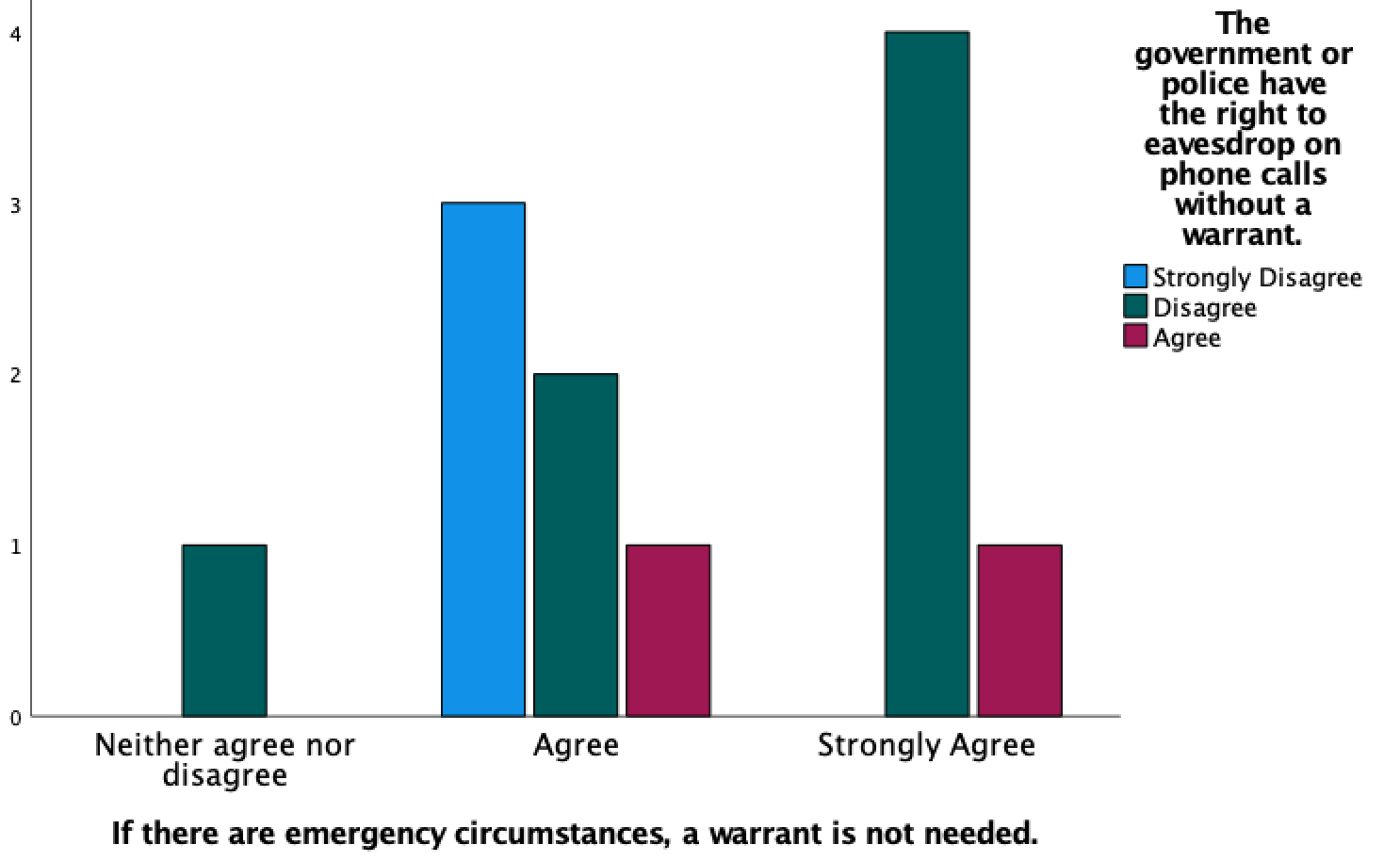

As an additional confirmation of the above assumption, it is worth quoting the results of the nonparametric Chi-Square test. This analysis was designed to assess the relationship between respondents’ attitudes toward law enforcement during emergencies and the ability to eavesdrop on phone calls. The results of this test showed that participants who did not think it was necessary to have a warrant during emergencies mostly disagreed with the possibility of phone tapping by the authorities. The result was statistically significant, which means there is a possibility of extrapolating the results to the population. This creates a paradoxical picture in which virtually the same violation of constitutional law is differentially perceived by people depending on how that violation affects their lives.

Conclusion

The purpose of this research paper was to determine the state of public awareness of the Fourth Amendment. The Amendment bans all searches by law enforcement agencies in the absence of judicial justification, that is, in the actual absence of an appropriate warrant. Obviously, this awareness was intended to show the extent to which respondents appeared to be aware of the problem of the illegal invasion of privacy or, conversely, the extent to which they supported the primacy of national security ideas over the privacy of a citizen’s personal interests. To measure this awareness, an online survey was administered to 15 respondents. The purpose of this questionnaire was to determine not only whether individuals were familiar with the content of the Fourth Amendment but also to identify their attitudes toward specific situations. To do so, respondents were asked to rate their level of agreement on a five-point Likert scale with specific statements describing law enforcement actions in the event of a search, with or without a warrant.

The results of the statistical analysis, which included both descriptive and inferential statistics, showed exciting results. This result is entirely consistent with the first part of the working hypothesis of this project. In addition to expressing complete agreement with Fourth Amendment knowledge, all respondents were different about the legality of searches without arrest. One of the most intriguing results of this study, which raises many issues for discussion, involved determining the balance between the personal and the public. In particular, on the one hand, respondents agreed that a warrant was not necessary for emergency situations. This seems logical because, in natural disasters, martial law, or an act of terrorism, the national security of large numbers of people appears to prevail, meaning that it is in the interest of the authorities to protect their population (Sanfilippo, 2020). The sample showed that society tends to agree with this and give up its personal security for the sake of national security. On the other hand, the survey demonstrated that wiretapping by law enforcement without an appropriate warrant was perceived by respondents as illegal, that is, individuals perceived this behavior as unfavorable. This aspect should be considered from the point of view of personal security of own interests, that is, society is not ready to make concessions to the authorities in the absence of essential need: personal is more important than public.

However, the inferential analysis showed a paradoxical result for these respondents. Although they agreed that a warrant was not necessary for emergencies, they did not agree to give up personal phone calls for wiretapping without a warrant. One might postulate it differently: those respondents who did not allow authorities to use their phones without a warrant allowed searches without a warrant in emergencies. This shows the paradoxical thin line between personal and public safety and the possibility of a dramatic shift between the two when geopolitical, or natural agendas change.

It is easy to draw a parallel between respondents’ beliefs and how the Fourth Amendment works in actual practice. In the already discussed case of Ohio v. Smith, already discussed, the Ohio Supreme Court concluded that wiretapping without a warrant could only be justified when an officer is in danger, or an emergency occurs (Ward, 2011). In this example, one can see that the issues of personal and national security are once again at odds, with circumstances forcing law enforcement to sacrifice one for the other. When it comes to this balance, most studies consistently look to the tragic day of 9/11, which was a watershed moment in U.S. history (Hartig & Doherty, 2021). Obviously, if intelligence agencies had had an unfettered ability to search, such a tragedy could have been avoided. It can be assumed that it is this postulate that has become the root anchor for a society that does not want a repeat of such large-scale man-made disasters, so is willing to sacrifice some of its rights to the authorities in exchange for ensuring national security.

Thus, it is correct to postulate that the study has broadened our understanding of the Fourth Amendment problem with respect to the personal rights of citizens and illegal searches. The findings fully demonstrated the unresolved paradox of the balance of interests in society and the legal agenda, allowing the findings to be viewed as robust and representative. Resolving this conflict, while a high priority, is hardly a matter for the next few years or even decades. As long as society exists within the framework of the state and entrusts administrative functions to the authorities, such conflicting delegation will be relevant. In the context of the criminal case, the results show that issues of unreasonable searches remain maximally sensitive, which means that generalizations and extrapolations of law enforcement practices for searching citizens can be misguided and lead to destructive consequences.

Limitations and Recommendations

The study shed light on the topic of public awareness of the Fourth Amendment, but it has several limitations. First, the sample used for the survey was relatively small, which may contribute to a bias in the reliability of the results. Second, individuals to whom the invitation link was distributed were accepted to participate; there is no guarantee that the same individual took the survey only once. The Hawthorne effect that occurs in surveys, leading to skewed results due to respondents’ sense of controlling observation, should also be considered (Nguyen, 2018). Addressing these limitations is part of the future development work of the project.

In addition to working on the limitations, the research can be expanded to produce more comprehensive results. Precisely, changing the paradigm from cross-sectional to longitudinal would measure the extent to which public attitudes toward unwarranted searches are a constant. In addition, it would be interesting to know the differences in such perceptions among different demographic groups. For example, this could relate to identifying differences for respondents of different ethnicities or from professional communities. It is expected that such changes would greatly expand the scope of the project.

Reference List

Becknell, C. (2021). Constitutional law – Fourth amendment search and seizure-online schools during a pandemic: Fourth amendment implications when the state requires your child to turn on the camera and microphone inside your home. University of Arkansas at Little Rock Law Revie, 44(1), 161-192.

Bobber, B. J. (1985b). Fourth amendment. Warrantless search of packages seized from an automobile. The Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology (1973-), 76(4), 933-960.

Fourth Amendment. (n.d.). Web.

Hartig, H., & Doherty, C. (2021). Two decades later, the enduring legacy of 9/11. Web.

Justia. (2019). People v. Diaz. Web.

Justia. (n.d.). United States v. Ross, 456 U.S. 798 (1982). Web.

LII. (2020). Fourth amendment. Web.

Nguyen, V. N., Miller, C., Sunderland, J., & McGuiness, W. (2018). Understanding the Hawthorne effect in wound research — a scoping review. International Wound Journal, 15(6), 1010-1024.

Sanfilippo, M. R., Shvartzshnaider, Y., Reyes, I., Nissenbaum, H., & Egelman, S. (2020). Disaster privacy/privacy disaster. Journal of the Association for Information Science and Technology, 71(9), 1002-1014.

Schwinn, S.D. (2017). Does the government’s warrantless search and seizure of a cell phone user’s cell-site data from a cell phone carrier violate the Fourth Amendment? Preview of United States Supreme Court Cases, 45(3), 91-94.

Tokson, M. (2020). The emerging principles of fourth amendment privacy. The George Washington Law Review, 88, 1-74.

Ward, S.F. (2011). 411: Cops can read txt msgs. ABA Journal, 97(4), 16-17.

Appendix A

Instrument

Thank you for participating in this survey. The purpose of this study is to examine your perceptions of the Fourth Amendment and Warrantless Searches.

Thank you for your participation.

Please indicate your ethnicity:

- □ Caucasian

- □ Hispanic/ Latino

- □ African American

- □ Asian

- □ Other: ………………………

Please indicate your gender:

- Male

- Female

- Other………….

Please indicate your age group:

- □ 18-25

- □ 26-32

- □ 33-40

- □ 41-50

- □ 51+

Using the following scale, please evaluate to what extent you disagree or agree with the statements below: 1= Strongly disagree (SD) 6= Strongly agree (SA)

Thank you for your feedback!